The Vanishing Object of Technology

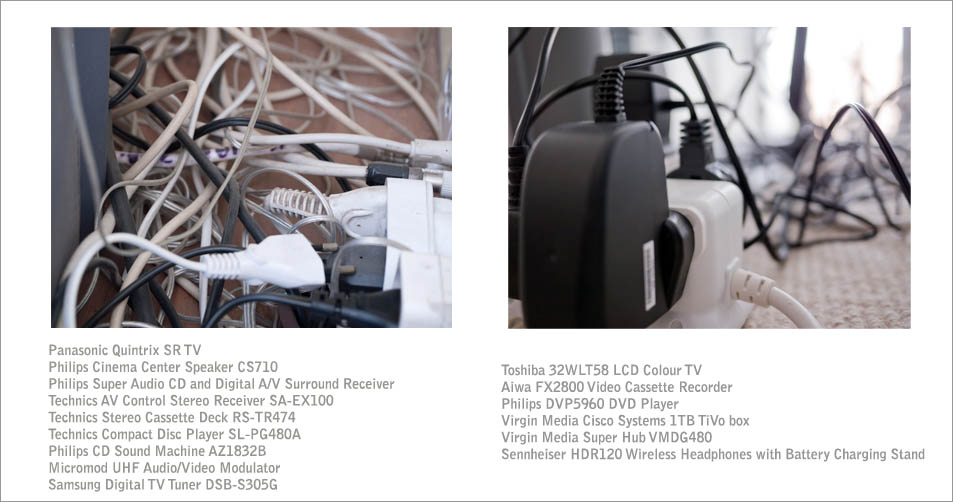

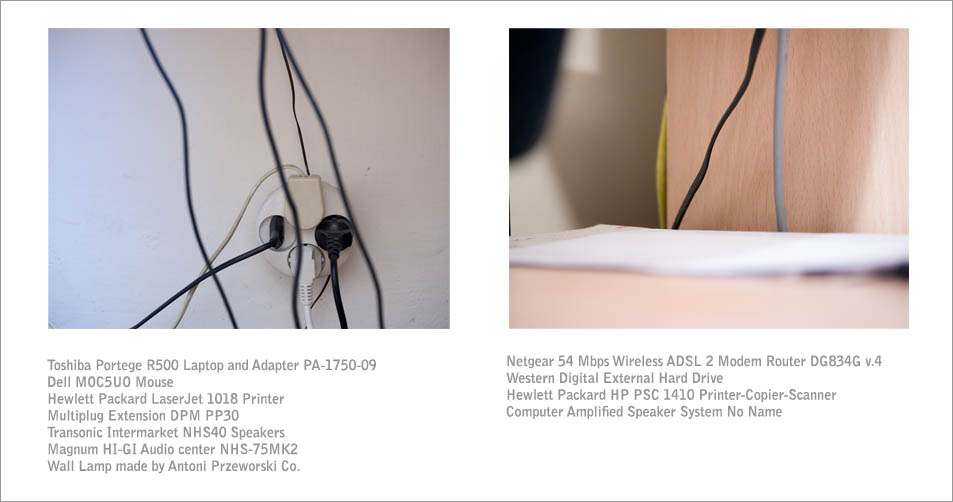

I have been photographing tangles of cables and wires in domestic and office settings since 2011. The drive for the project came from the increasing inconvenience I was experiencing when having to carry my laptop, iPad, mobile phone and camera charger, all spouting long leads—an inconvenience made even more pronounced by frequent travel in which half my luggage space is taken up by a bunch of wires. But I have also become ever more fascinated by the tangled dusty arrangements behind or underneath both my own and other people’s desks and TV sets, with numerous devices such as monitors, speakers, external hard drives, printers, scanners, DVD or Blu-ray players, satellite or cable TV boxes, additional USB ports, extensions, and other pieces of equipment (some of which may have become obsolete but which cannot really be removed for the fear of disrupting the setup) all connected to form a wiry sculptural mess. Yet the project is aimed to be more than just a nostalgia trip inspired by the supposedly vanishing technology or a retro-fashion tribute aimed at reminiscing about ‘old media’ just for the sake of it. Nor do I want it to be a celebration of the brave new world of improved technological design, or even a prediction of wirelessness as a new technological condition, which Adrian Mackenzie describes in his eponymous book. My ambitions are much more modest and, one might even say, minimal: I just want to stabilise that moment of thegradual disappearance of wires from our human view. The images presented here thus offers a poetic meditation on the changing ecology of our everyday technical setups. Combining shots from underneath my desk taken over a period of one month into an installation of lines, grids and traces, it proposes an intertwined textual and visual engagement with a unique moment in the history of technology.

It is precisely this extensive tying and knotting of wires as stabilised into unwitting sculptural objects that is of interest to me. Wire tangles and knots serve as a testament to the everyday struggle between order and chaos in everyday media ecologies. They are intrusions into the oft minimalist or functionalist arrangements of living or work spaces, a material reminder of the excess of the everyday that cannot be swept away. They also reveal a unique slippery-obstinate tactility, one we encounter when trying to tidy them up, or tidy up around them—that is, when trying to bring order into what is inherently a disorderly arrangement. We could perhaps go so far as to say that this aesthetic presencing of the wired tangle thus has an ethical dimension, too: it is a demand placed on the human inhabitant of domestic or office spaces by second-rate objects connected to other objects. And therefore, even though aesthetic arrangements are something that has caught my attention, literally and photographically, it is the ethical call of these arrangements that is really of primary concern to me. While I do recognise, together with other theorists of postanthropocentric thought, that ‘it is not all about us’, I also recognise the singular human responsibility that is exercised both by philosophical theory (which is consciously undertaken by few) and philosophical practice (which is a much more widespread undertaking, even if not always a conscious one). The ethics of expanded obligations becomes a way of taking responsibility for the world around us and of responding to the tangled ecology of everyday connections and relations (see Zylinska, 2009).

This is indeed where image-based practice such as photographic work performed with a camera stops being just an aesthetic endeavour and opens up a passageway to ethics. It is a way of signalling that turning images of wired tangles into photographs is a way of visualizing these acts of presencing of the world, this demand that objects in the world place upon us, and also of carving and slicing the world in a particular way as both a violent and a pragmatic gesture of arranging the world into particular setups. Photography can be a way of reminding ourselves of there being setups in the first place by stabilising and hence creating them as setups—such as these particular ones seen here, which we have coordinated at a certain scale by connecting equipment in this and that way—and yet open to so many different influences and activities: production, transfer of particles of electricity, linkage to objects, systems and bodies we are not familiar with or cannot even envisage. The wired tangles are, then, more than just symbols: they are actual bundles of connections, foregrounding some links but also hinting at other invisible ones across different scales. They thus serve as a reminder to us that there is life behind a machine; that, as Jane Bennett puts it, ‘deep within is an inexplicable vitality or energy, a moment of independence from and resistance to us and other bodies’ (2010: 12).

References

Bennett, J. (2010) Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Mackenzie, A. (2010) Wirelessness: Radical Empiricism in Network Cultures. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Zylinska, J. (2009) Bioethics in the Age of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Joanna Zylinska, The Vanishing Object of Technology II, 2012.